The discovery of the Library Cave in the Mogao Grottoes in 1900 revealed a hidden history of ancient China. As “one of the greatest archaeological discoveries in the 20th century”, it also made Dunhuang well known to the world.

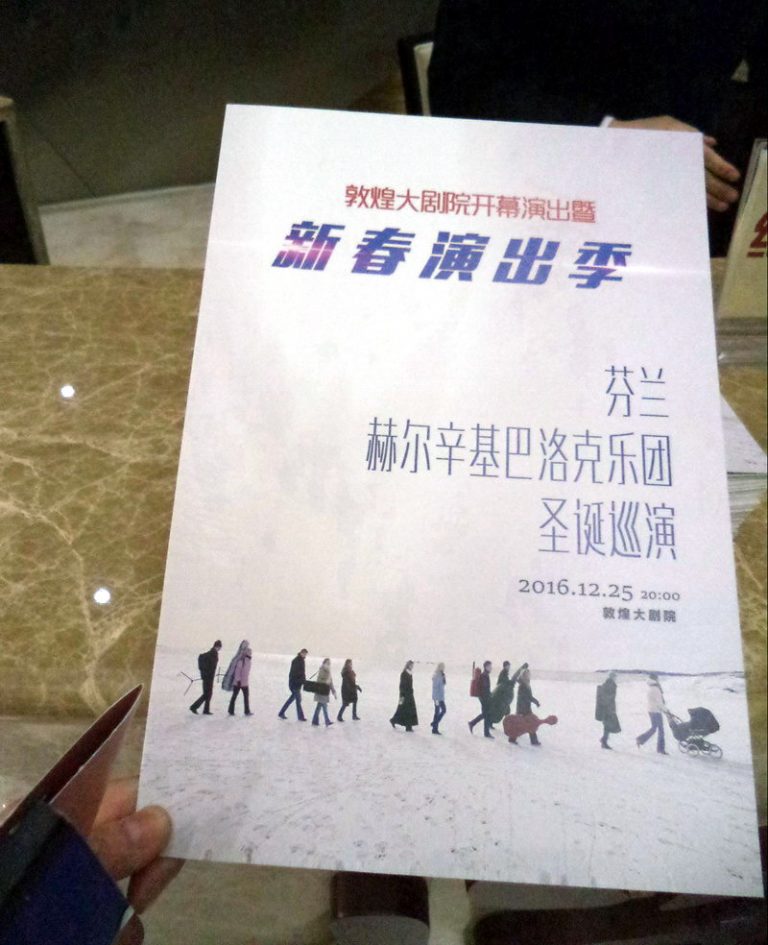

Today after over a century has passed, the local residences are benefitting from the discovery more and more, not only in the economy but something beyond, as the Helsinki Baroque Orchestra paid their first visit to the town on Christmas Day of 2016 for the opening season of the Dunhuang Grand Theater…

DUNHUANG 12/25: the First Western Holiday in Western Music

By TAN SHUO January 12, 2017

At 6:45 pm on December 25, 2016, the Dunhuang Grand Theater saw Helsinki Baroque Orchestra walking on the stage for a brief rehearsal. Later, they were going to give their closing concert here of their very first tour in China.

Meanwhile, the melody of Jingle Bells from the loudspeaker in the foyer was trying hard to penetrate the gates of the hall, seeming to remind everyone of a western holiday today. Yet no one in the rehearsal was really distracted. The joyful carol was apparently not for the Finnish musicians, but to welcome those who were making headway toward the venue in a freezing cold of minus 7 degrees.

The theater, which was completed construction a few months ago on August 18, 2016, is situated over five kilometers away from the town — a distance never means short to the locals. In other words, no one could come by public transport, for the city buses have not yet reached that far.

Nevertheless, people were seen coming — one after another, more and more. They were at all ages, including many children in high spirit, who later turned out to be surprisingly quiet during the concert.

In fact, most of the audiences, whether the adults or the youngsters, well presented themselves with customary aplomb for classical music appreciation.

“Dunhuang people are relatively reserved,” told Minna Kangas, concertmaster of Helsinki Baroque Orchestra, when comparing their evening at Shanghai Oriental Arts Center the day before.

Like most of the theatres in China, there was no organ in the Dunhuang Grand Theater, either (let alone harpsichords), hence Anna-Maaria Oramo had to play her organ solo (Vivaldi’s Pastorale) at a Casio digital piano. Perhaps, it was the reason that the first half of the concert was alight at violinist Dmitry Sinkovsky’s countertenor voice.

When handsome Sinkovsky with his ponytail unlocked strode onto the stage and started the first note of Vivaldi’s motet Longe Mala, Umbrae, Terrores, the whole audience — although knowing his “double identity” as both violinist and singer — was still stunned. The tempo was dealt with more swiftness, therefore more technically demanding, yet it was well under Sinkovsky’s mastery.

Two-seat away right from me sit a young voice teacher from the affiliated school of a local oilfield institute. He subconsciously leaned forward and attended closely to Sinkovsky until the song of over 10 minute long finished.

The organ solo of Silent Night opened the second half of the concert and it shifted to Vivaldi’s Winter without a break. The intro of Winter vividly crafted by the Helsinki Baroque Orchestra seamlessly connected the two pieces and all the three movements were imbued with the similar liveliness. “For us, it’s always like being a ‘choreographer’s to make your own picture of what Vivaldi wanted to say,” told Sinkovsky in the interview after the concert.

The audience always gave applauses between the movements, but as soon as they realized the music was still on, they cut off immediately with slight self-deprecating laughter.

When Winter was gone, a set of Polska (Finnish folk baroque music) led everyone to enter a world of warmth and cheers. The red Santa hats of the musicians as well as their interactive way of playing added special flavors. What’s more, their free spirits in the improvisation accompanied by the accelerando-crescendo footsteps did resonate with the audience, for it has something in common with the folk music of the local region.

The concert culminated in the final piece Il Great Mogul, in which Sinkovsky showcased his virtuosity particularly in the last movement and gripped everyone in the hall.

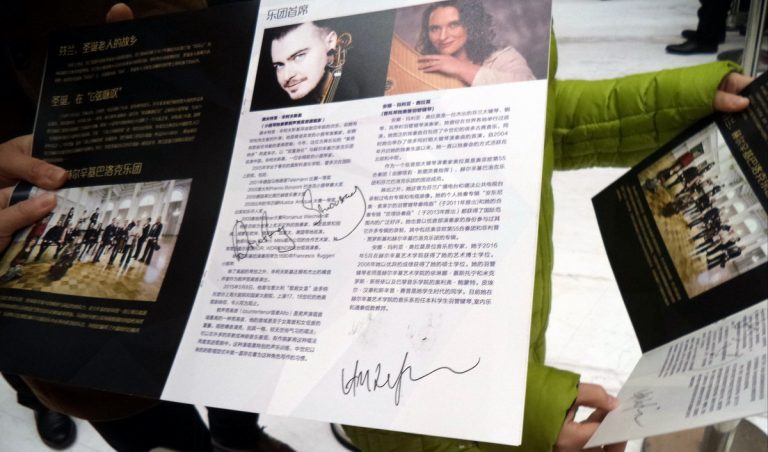

After the concert, the Helsinki Baroque Orchestra came back to the stage twice for curtain calls, but they did not give encore anymore. Probably they were too tired, for they flew to Dunhuang from Shanghai that day — a trip of 3,000 kilometers. Whereas Sinkovsky and violinist Aira Maria Lehtipuu on the orchestra behalf patiently met the demand of the excited audiences for autographs afterward.

On Christmas Day, the most important western holiday of the year, nearly a thousand Dunhuang people attended a live western music concert given by a western orchestra first time in their home city theater.

On my way back to the hotel, I recalled the mother whom I met before the concert at the stairway of the hall. In the summer of 2015, she traveled to Beijing with her school daughter and took the chance to attend a choir concert at the National Centre for the Performing Arts. Her memory of that concert was still fresh, yet since then she had not listened to another.

“Here (Dunhuang) is unlike the ‘Inland’,” she said, “Chances are too few…”

It is uncertain that how satisfied the mother and her daughter were with the concert of the Helsinki Baroque Orchestra — “a concert at the door of home” as she described. Nor is it clear what memories will leave in their mind. Yet one thing is sure that: to be audience again, they do not have to wait up to one year and a half anymore.

© TANTANYY

For Audiences, Artists, and Theatres